The Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabees, Antonio Ciseri, 1863, Oil on Canvas, St Felicita, Florence, Italy.

One of Satan’s wiles is the distortion of words, so that they lose distinctions and create confusion where previously there was clarity. That this would happen is predicted in Isaiah.

Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter! (Isaiah 5:20)

One of the words under attack in our time is ‘martyrdom’.

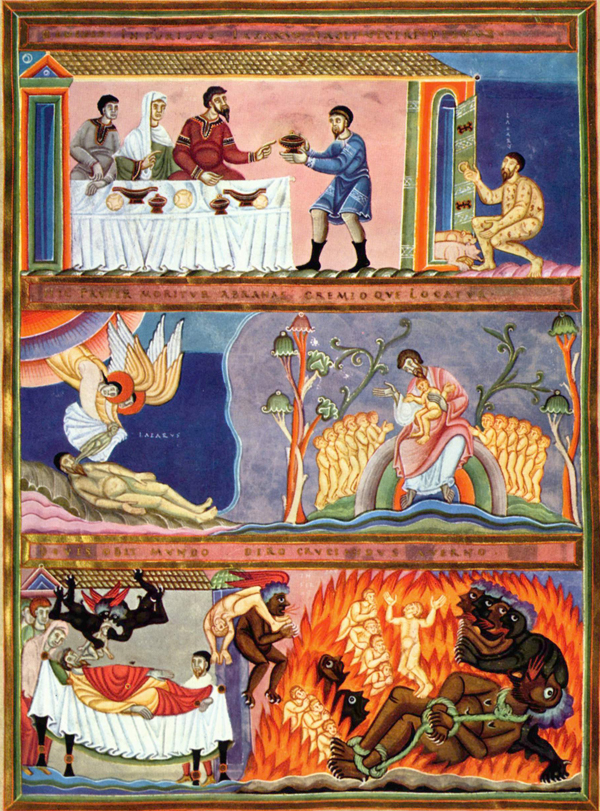

We have a superb, if gruesome, illustration of the traditional meaning of martyrdom in today’s Old Testament reading from 2 Maccabees. In fact, this is one of the first descriptions of martyrdom in a distinctively Jewish context, aside from prophetic accounts such as Isaiah’s Suffering Servant passages.

The setting is the Greek empire during the period after the death of Alexander the Great, when the empire was split between the northern Seleucids (Mesopotamia, Persia – Iraq and Iran in our day – and Syria) and the southern Ptolemies (Egypt and Palestine). Antiochus IV, king of the Seleucids, a man seized by a thirst for power, wrested control of Palestine away from Ptolemy IV, Pharaoh of Egypt, in 169 BC. In an extraordinary display of self-aggrandisement, he assumed the title “Theos Epiphanes” or “God Manifest”. He then set about a systematic destruction of Jewish culture and religious practice. The aim was to unify the territory he controlled by replacing the ‘backward’ religious beliefs and observances of the Jews with ‘enlightened’ Greek (Hellenistic) culture and religious practice. He attacked the temple, carrying off its altar and sacred vessels, pillaged the city and tore down Jerusalem’s wall that had been rebuilt by Nehemiah after the Babylonian captivity, took women, children and cattle captive, and rebuilt the city with a stronger wall and a Citadel.

The king then issued a proclamation to his whole kingdom that all were to become a single people, each nation renouncing its particular customs. All the gentiles conformed to the king’s decree, and many Israelites chose to accept his religion, sacrificing to idols and profaning the Sabbath. The king also sent edicts by messenger to Jerusalem and the towns of Judah, directing them to adopt customs foreign to the country, banning burnt offerings, sacrifices and libations from the sanctuary, profaning Sabbaths and feasts, defiling the sanctuary and everything holy, building altars, shrines and temples for idols, sacrificing pigs and unclean beasts, leaving their sons uncircumcised, and prostituting themselves to all kinds of impurity and abomination, so that they should forget the Law and revoke all observance of it. Anyone not obeying the king’s command was to be put to death. Writing in such terms to every part of his kingdom, the king appointed inspectors for the whole people and directed all the towns of Judah to offer sacrifice city by city. Many of the people – that is, every apostate from the Law – rallied to them and so committed evil in the country, forcing Israel into hiding in any possible place of refuge. (1 Maccabees 1:41-53)

To the horror of the Jews, sacrifices to Olympian Zeus were made in the Temple on the Altar of Burnt Offering on the 25th of each month, (2 M 1:59) any copies of the Torah that were found were torn up and burned, and women who had had their children circumcised were put to death with their babies hung round their necks.

Today’s reading from 2 Maccabees gives us a vivid portrayal of a particular family of Jews who resist this ideological colonisation. Seven brothers and their mother are arrested and tortured to force them to taste pork. Their eldest brother has his tongue cut out, his head scalped and his extremities cut off before he is fried while still alive in a red-hot pan before his brothers and mother. Slowly the torturers make their way through all the brothers and finally the mother. With remarkable courage they stand firm in their resolution to be faithful to the Torah and their covenant relationship with God. You might wonder why they didn’t just eat the pork – it’s only food after all. But to the Jews, adherence to the dietary laws was not just a meaningless dietary restriction. It was symbolic of their relationship of familial trust, love and duty towards the God who had formed them and led them since earliest times.

Now what is remarkable about their martyrdom is that they see it, not as a failure, but as the occasion for a number of opportunities, namely,

- An opportunity to participate in the future, bodily resurrection:

“Ours is the better choice, to meet death at men’s hands, yet relying on God’s promise that we shall be raised up by him; whereas for you there can be no resurrection to new life.” “Cruel brute, you may discharge us from this present life, but the King of the world will raise us up, since we die for his laws, to live again for ever.”

- An opportunity to explain God’s plan for his people and his intervention in human history.

“You have power over human beings, mortal as you are, and can act as you please. But do not think that our race has been deserted by God. Only wait and you will see in your turn how his mighty power will torment you and your descendants.”

(In fact, within 5 years, Antiochus IV is dead, and within 100 years, the Greek empire is overcome by the Romans under Pompey.)

- An opportunity to die to self – to give up concern for one’s own safety and security to uphold what is good and true.

“Heaven gave me these limbs; for the sake of his laws I have no concern for them; from him I hope to receive them again.”

- An opportunity to atone for the sins of their fellow Jews; they are able to redeem the sins of other people by taking on suffering themselves:

“Do not delude yourself: we are suffering like this through our own fault, having sinned against our own God; hence, appalling things have befallen us.”

- An opportunity to show profound humility and trust in God’s ultimate plan. The mother says,

“I do not know how you appeared in my womb; it was not I who endowed you with breath and life, I had not the shaping of your every part. And hence, the Creator of the world, who made everyone and ordained the origin of all things, will in his mercy give you back breath and life, since for the sake of his laws you have no concern for yourselves.”

Now contrast all this with the other kind of (self-described) martyrdom, the kind on display so frequently these days among terrorists. The type of martyrdom that says you can kill yourself in the name of religion. When a terrorist blows himself up, hoping to take as many others with him as possible, this is as unlike a Jewish or Christian martyrdom as it is possible to get. If there is anything in common between the two ‘martyrdoms’, it is the zeal and commitment of the participants, but that is all. It is possible to make several distinctions between these martyrdoms:

- Judaeo-Christian martyrs have historically been innocent victims. The martyrs of Islamic State are perpetrators of terror and cruelty, not victims.

- Judaeo-Christian martyrs give up their own lives in non-violent surrender to the violence of others. They do not seek death, merely surrender to it when death becomes inevitable. Martyrs of the Islamic State actively seek death and are effectively committing suicide.

- Judaeo-Christian martyrs see their suffering as redemptive. Their willingness to undergo suffering is an atoning sacrifice which has a redemptive effect. Witness how the Holocaust of World War II led to the reversal of the Jewish diaspora and the re-creation of Israel. Witness how the blood of the early Christian martyrs was the seed of the Church.

- The heavenly reward that Judaeo-Christian martyrs hope for is one where they will be united with God in a living relationship of selflessness, perfect love and joy in His presence … the reward that the martyrs of ISIS hope for seems to be focused on selfish pleasures and unbridled lust – men being rewarded with 72 virgins, for example.

These are just a few differences; others could be found. Right now, there is an unprecedented number of Christian martyrdoms occurring, particularly in the Middle East and Africa. The perpetrators are ISIS, Al Quaeda, Al Shabaab, the Taliban, Boko Haram, Wilayat Sayna, Lashkar-e-Taiba and their ilk. Many of these go unreported by a media that is hostile to Christianity, but you can easily find them here. Right now, the state of Christian martyrdom in the world is so dire, that we pray that God will soon end this torment and restore the world to himself. May the blood of the real martyrs atone for the sins of a world that has abandoned God in so many ways, and may God strengthen us to resist any attempts of the state to restrict religious freedom.

Today’s readings:

Word format: year-c-32nd-sunday-2016

Pdf format: year-c-32nd-sunday-2016

The Catholic Church of Yanchep will be holding a prayer vigil and Mass today, 22 October, with the special intention of praying for the

The Catholic Church of Yanchep will be holding a prayer vigil and Mass today, 22 October, with the special intention of praying for the

If you thought being a Christian was a life of pure unadulterated blessing, think again. Sure, you will receive many blessings along the way, but

If you thought being a Christian was a life of pure unadulterated blessing, think again. Sure, you will receive many blessings along the way, but