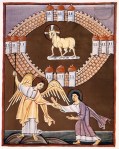

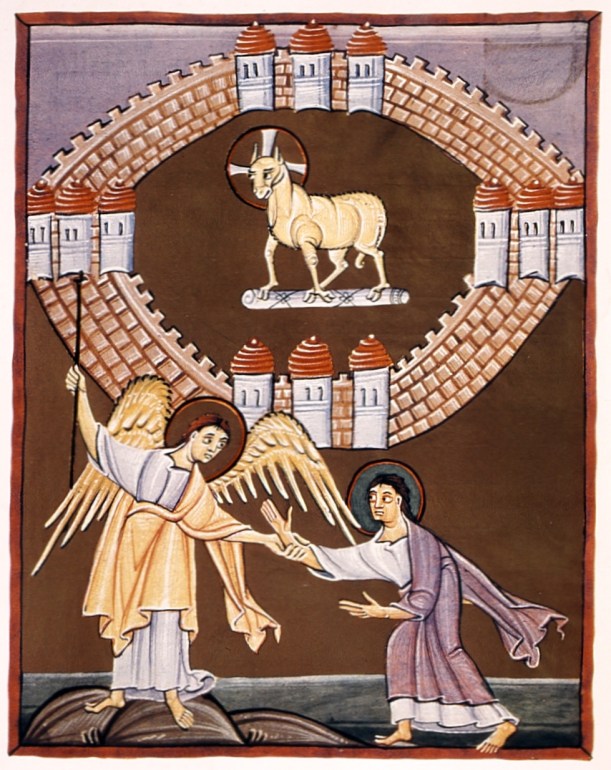

The New Jerusalem, Bamberg Apocalypse, 11th century, Folio 55, MS A.II.42, Bamberg State Library, commissioned by Otto III.

Today’s Gospel reading may at first sight seem a bit repetitive. But remember, John has a purpose in everything he writes. He tells us he could have written a whole lot more, but he has selected what he has, ‘so that we might believe’ (John 20:31)

The words he keeps repeating are ‘glorify’ (ἐδοξάσθη) and ‘love’ (ἀγάπη).

Why does Jesus say ‘Now has the Son of Man been glorified?’ What has just happened? Judas has just received the Eucharist and slipped out of the room to deliver Christ to his enemies! (verse 27: At that instant, after Judas had taken the bread, Satan entered him).

It seems as if John has made a typographical error. Didn’t he mean ‘Now has the Son of Man been betrayed?’ But no, John wants us to understand that the Glory of Christ is in his willingness to undergo betrayal by a close friend, with all that comes afterwards.

The next few lines read like a poem on the Trinity. Everything that affects the Son, affects the Father. Everything of the Father reflects back to the Son. It’s almost mathematical in its expression. Let a = Son and b = Father. x = glorification. If a has property x, then b has property x. If b has property x, then a has property x, or to put it in the way John puts it:

Now has the Son of Man been glorified,

and in him God has been glorified.

If God has been glorified in him,

God will in turn glorify him in himself,

and will glorify him very soon.

Jesus turns the focus from this great act of betrayal by Judas into God’s great act of self-giving. Self-giving is God’s glory.

Jesus is adding a whole new dimension to glory, usually understood as God’s holiness, majesty and power. How could it be otherwise? If God were selfish, he would not be glorious. If God wanted us to love him merely because of his overwhelming power as Creator, that would not constitute greatness. But a God who loves to the point of allowing himself to experience the most excruciatingly egregious behaviour of his creatures, and giving up everything he has by right, truly deserves our praise and respect.

In this passage the Son, the Father and the Holy Spirit are all present. Where is the Holy Spirit? He’s not actually mentioned. But we know the Holy Spirit appears as a Cloud of Glory (the Shekinah cloud) elsewhere in Scripture. And here John’s crescendo of glorification words describes what amounts to a verbal Cloud of Glory around the Father and the Son: what is this if not the Holy Spirit, the love between the Father and the Son?

Today’s readings (Australia):

Word format: Year C Easter 5th Sunday 2016

Pdf format: Year C Easter 5th Sunday 2016